Why do they call it the blues? Blue is the color of the sky, which symbolizes transcendence of earthly labors and woes. To be blue is to yearn to be free, whole, and complete, but to have that longing abort. It is to long to soar into the sky of hopeful possibilities, but to have life’s disappointments leave one earthbound.

What follows is a very incomplete analysis of the experience of being blue, melancholy or depressed. Our search for clues will take us to Abraham Lincoln, to an old 1960s song, to Casablanca and then back to Lincoln.

—————————————————-–

Consider those occasions when you’ve been down, depressed, or had the blues. What have they in common? They emerged out of the gap between what you wished life to be and what it actually is. You might, for example, have hoped that someone you love would love you in return, but your affection goes unrequited. Or you would like life be fair and just, but it’s often quite the opposite. Or you wished that your pet collie could have lived forever, but it had to die, like all mortal beings.

That gap feels like a fissure in your world, a black hole sucking all dreams of a happy life into oblivion. The particular disappointment, setback, or tragedy you experienced made your world no longer seem a place of hope and possibility, but a broken, or fallen world, a wasteland. In the words of Matthew Arnold:

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.Here’s the curious thing: the perception of the fundamental gap — between the ideal and the real — doesn’t always engender tragic sadness. Sometimes, it results in laughter. Consider any comic situation, whether it be from a play, film or TV series. The real belly laughs come from the gap, or discrepancy, between what the protagonist attempted to accomplish and what actually befell him or her.

Obviously, it is more pleasant to laugh at the gap than to cry about it. What, then, the tears? Horace Walpole offers us a clue when he writes: “Life is a tragedy for those who feel and a comedy for those who think.” Are feelings, then, the culprit?

Of course, it is one thing to be occasionally sad or even to be temperamentally disposed to sadness. But it’s another matter to feel blue for long periods of time, with little or no respite, as in the case of melancholy, or depression. Might it be that those who suffer from chronic depression tend to dwell in their feelings?

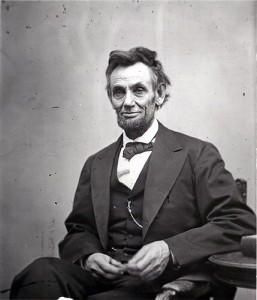

Lincoln’s Melancholy

The life of Abraham Lincoln might offer us some clues to the mystery of depression. Lincoln suffered throughout his life from melancholy. His life might afford us some insights into that affliction. According to historian Joshua Wolf Shenk, in an article entitled “Lincoln’s Great Depression” (Atlantic Monthly, October 2005), Lincoln’s depression was pretty much continual and it was serious. It was serious enough, according to Shenk, that Lincoln would often talk and write of suicide.

Lincoln had a powerful intellect and was of course a deep thinker, which might lead one to conclude — by Horace Walpole’s reasoning — that Lincoln viewed life as a comedy. But, that is not so, for Lincoln was a man with strong feelings, especially those that arise de profundis, from one who knew heartbreaking calamities from his early years. His sentiments were also a function of compassion, which latter found expression in his second inaugural address: “With malice toward none; with charity for all…”

There is no denying the truth of the tragic vision of life, that the world is a “veil of tears,” but heartfelt caring need not lead to melancholy. It can lead to the effort to redeem our fallen world. Furthermore, decisive action is an antidote to melancholy and Lincoln certainly acted decisively. Comedy, too, is an antidote, and Lincoln was an avid collector of jokes and funny stories. How, then, are we to explain Lincoln’s chronic depression? Indeed, how can we explain any persistent depression?

We are back to the question of feelings. Are dark feeling, such as melancholy, addictive in some way? If they are, they must fulfill some psychological need. Perhaps sadness is orienting in its constancy. We might say: Same gloom, different day. We know what’s coming. The danger, of course, is that we might, when we least expect it, be surprised by joy. Certainly, joy is one of the most disruptive of emotions.

The End of the World

Music has the power to stir up emotions and feelings. That, according to Plato, is dangerous, who would have us live the life of reason. In so far as songs make us feel, do they evoke, by Horace Walpole’s logic, the tragic sense of life? Not at all, for not all songs are sad, or in a minor key, but as Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote: “Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thoughts…” Back in 1965, Skeeter Davis sang a plaintive love song called “The End of the World,” which includes the lyrics:

“Why does the sun go on shining?

Why does the sea rush to shore?

Don’t they know it’s the end of the world,

‘Cause you don’t love me any more?”

“Don’t they know it’s the end of the world?

It ended when you said goodbye.”

Here the song on youtube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qgcy-V6YIuI

One could substitute any lost hope for the romantic one that is the subject of this song. Although it might be a bit less lyrical, one could say: “How does the sun go on shining? It ended when I failed to make junior partner at the law firm of Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz.” Or “It ended when the town’s zoning commission turned down our application for an easement, which would have allowed us to open a hotdog concession across from City Hall.” Or “it ended way back in 1957, when the Dodgers left Brooklyn.” It can be anything that should have happened, but didn’t, or that didn’t happen, but should have. Either way, it creates the gap, that we discussed earlier, between the way life should and the way it is.

Most of the time, we soon get over such passing disappointments, but to be depressed is to allow the disappointment to feel like the end of the world and an occasion for eternal gloom. Moroseness involves a self-indulgent clinging to despair. That clinging prevents the buds of a new life from allowing something new to emerge.

We cling for we fear an apocalypse of a deeper sought, one in which we are called upon not just to passively be in despair, but to actively despair, to use Kierkegaard’s language, of our present way of living. It means to “put away childish things.” When that happens, it really is the end of the world, as we know it, which can be a very good thing.

In Skeeter Davis’ song, the world doesn’t really end for the lovelorn woman. Rather, the world has a fissure, or hole, in it, the correlate to what people mean by a broken heart. And so she wonders how the sun can go on shining and the world can continue to exist. Indeed, she is puzzled how it is that objective reality belies her inner state of sadness. The contrast between inner and outer even creates a certain wonderment, which might even launch a philosophical question.

In any case, there may come a point, in our inner-development, when our world, whether it be fallen or not, must really end, in a very real way. More specifically, our particular mode of existence — and the world we create, which is a product of who we are — must come to an end, so that something new can emerge. It must end in the way that a dream must end, when it is time for the dreamer to awaken.

In the film Casablanca, Rick went through a long period of bitter melancholy and despair following

his romantic disappointment in Paris. When he sells his restaurant and go off to war, it’s the beginning of a new life for him.

Thus, oftentimes, the end of the world is the end of the life that we have been living. It may, more specifically, be the end of a career, a marriage, etc. But, more essentially, it is the end of a certain mode of existence, the end of a certain worldview. Might we say, then, that the clinging to past dreams — which are the fabrications of outmoded ways of being and seeing — after it’s time to awaken, is the ultimate source of melancholy?

Kierkegaard argues that melancholy is a hysteria of the spirit. When the spirit is ready to transform, it faints out of dread before the terrifying openness of freedom. Might our fainting — and falling back into the grounding darkness of feeling — be a flight from spiritual freedom and the key to melancholy?

Addendum: On the Sadness that Arises from Compassion and How It Needs to Be Balanced with Wisdom

Not all sadness, melancholy, or depression arises from compassion. But it does, in some instances, as in the case of Lincoln’s melancholy. Compassion is a feeling and we should remember Plato’s warning about the dangers of the emotions and feelings. And yet, feelings can be elevated to a very lofty level. We see that elevation, or sublimation, in the lives of noble souls, in great works of art, literature and music, and in Lincoln’s speeches. In his

First Inaugural Address, he wrote:

“Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

Lincoln meant by “mystic chords of memory” that the sacrifices by patriots and soldiers connect to our everyday lives as Americans. But it might be fair to say that bonds of affection and mystic chords connected Lincoln to the entirety of human suffering.

Is it possible to be attuned to those “mystic chords of memory” without being knocked over by tidal waves of fellow-feeling? For those waves can drown one in melancholy, as they often threatened to drown Lincoln. What’s required is a difficult balancing act. Certainly, those bonds of affection didn’t prevent Lincoln from defeating the Confederacy by whatever means possible, including having General Sherman burn Atlanta to the ground and all else in his path. So Lincoln’s affection for his fellow man was not sentimental, but was made of sterner stuff. His compassion was tempered by a keen perception of life’s sometimes agonizing realities.

Apropos is Mahayana Buddhism, whose goal is to balance compassion (karuna) with wisdom (sunyata). Wisdom, in this case, is not simply a sober-minded acknowledgement of life’s realities, but mystical insight into the ultimate emptiness of all phenomena.

But what a paradox! It means awakening to the unreality of the world and of the self, and to the illusoriness of human suffering and yet to devote ones life to ending that suffering. How does one devote one’s life to ending that which — according to the deepest insight — does not really exist? Such is the paradoxical task of the Bodhisattva, he who awaken others so as to release them from their suffering.

A well-balanced life really calls for us to accomplish difficult feats of equilibrium. In addition to balancing compassion and wisdom, life calls upon us to balance this-worldliness and otherworldliness. That, too, is quite an accomplishment — no matter what one does for a living and no matter what one’s role in life may be — for worldly affairs have a way of making us lose awareness of the big picture, such that the world, as Wordsworth wrote “is too much with us.”

It takes a Marcus Aurelius to balance active life in the world (he was emperor of Rome) with being a profound philosopher. And in the Bhagavad-Gita, it takes a mystical intuition for Arjuna to be both warrior and sage. Balancing acts are significant accomplishments, for the rope we must tread hangs over the abyss of despair.

The historical evidence suggests that Lincoln never overcame his proclivity for melancholy. But history also suggests that Lincoln found his balance, among life’s polarities, as he walked the path that leads to glory and salvation.

The sadness that grows out of fellow-feeling cannot be avoided, nor should we attempt to do so, for as Franz Kafka advised: “You can hold yourself back from the sufferings of the world, that is something you are free to do and it accords with your nature, but perhaps this very holding back is the one suffering you could avoid.” In any case, melancholy is another matter. Unlike sadness, who visits for a time and eventually departs, melancholy seeks to become a permanent resident of one’s heart.

Anyone on life’s journey is likely to encounter the demon of melancholy. The best defense is to illuminate the dark demon with the light of insight and understanding. The light will cause the demon to wither, like a witch that’s been drenched with water. Then, we should prompt the weakened demon to flee, by evoking the spirit of laughter. (It is not advised to skip step one, for laughter without insight is not powerful enough to exorcise the demon.) Having subdued the demon, we can continue on our journey. But we must stay on guard, for the demon of melancholy shall bide its time, waiting for another opportunity.

P.S. I can imagine the response of many a reader — including many a therapist — to my analysis of melancholy: “Balance, shmalance! Lincoln Sminkin! My depression is purely chemical. I’m a victim! So just prescribe me some Prozac. Let me remain in life’s shallows!” The problem is that perplexing questions are like sharks. From time to time, they swim from life’s depths into the shallows. And then they gleefully consume those who inhabit those waters.